Pacific Northwest peoples have lived along the Inside Passage for 7,000-10,000 years. What attracted them to this area was the abundance of fish, berries, furs, marine mammals, shellfish, waterfowl, copper, wood and fresh water. With so much bounty easily at hand, the Northwest peoples could easily preserve foodstuffs for winter, allowing time for leisure, storytelling, celebrations and art.

It was this combination of resources and leisure that attracted and held the native populations in this coastal area.The Haida natives occupied the Queen Charlotte islands and the lower part of the Prince of Wales Island. The Tlingit natives occupied the largest territory, along the coast from Yakutat Bay to Cape Fox.

Not much is know of those ancient native cultures.Theirs was an oral tradition, they had no written language. Ceremony and storytelling were the ways that their history was passed down.

We had visited the historical village at ‘Ksan, in Hazelton, BC, but it was when we saw the displays at the Totem Heritage Center, that we had one of those ‘full circle’ moments and it all kind-of ‘clicked’. And….we could take pictures! Then, we visited the reproduction Clan House at Totem Bight, and were able to appreciate the ‘authenticity’ that had been achieved.

In this photo from the Heritage Center, Tlingit natives are dressed in ceremonial garb.

This is a photo of a ‘button blanket’. This style of ceremonial robe became popular with the arrival of the first Europeans and new materials and trade goods. The hat is a traditional woven hat; the shape was highly efficient at shedding water in a rain.

This is a wonderful display of ceremonial masks. At ‘Ksan, the masks were not in a display case, but were worn by their native dance group for their Friday evening dance performances which are held in July and August.

Both the Haida and the Tlingit lived in plank longhouses in the winter.

These were constructed of log timbers and cedar planks, with a sleeping platform along the sides and a fire pit in the center. Several families would share one house, as only the more wealthy people could afford to build a large longhouse. This is a photo of the reproduction Clan House built at Totem Bight.

The Tlingit and the Haida are matrilineal societies; that is, they trace their lineage through the mother’s side of the family. They Tlingit peoples are divided into two basic matrilineal groups (or moieties), which have the totems of the Raven and the Eagle (or the Wolf, depending on the time period). The Haida are also divided into two basic groups, with the Raven and the Eagle totems. Each individual has a moietie totem and a family totem. These would be displayed on posts in the house, or on a totem pole erected in front of the house.

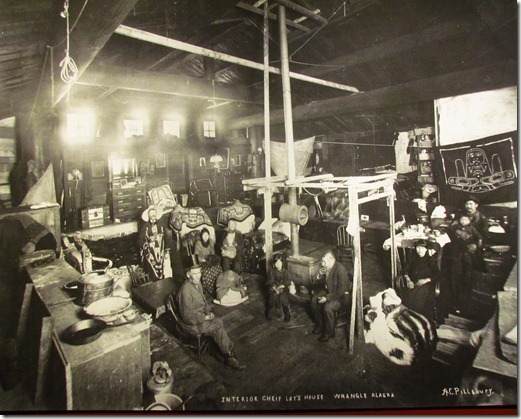

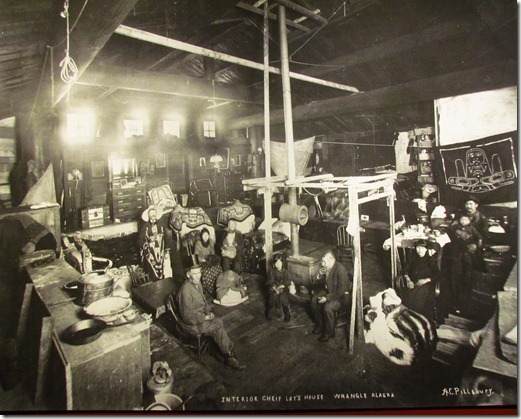

This photo shows the inside of a chief’s house, circa 1800’s. Note the mix of native and European furnishings. A wood stove has replaced the fire pit.

The red cedar was considered to be the native ‘life tree’ as it gave the people the materials for building, carving, artwork, tools, canoes for transportation, planks for making bent wood boxes, and strips of bark for weaving.

The bent wood box on the left was fashioned from a single cedar plank which had been soaked in water and heated and softened until it could be ‘bent’ into a box shape. These boxes were used to store food or belongings, and undecorated ones would be used for cooking (by filling with water and dropping heated rocks into them).

Weaving was an art form as well as a necessity. It was, literally, a ‘cradle to grave’ association. Infants were birthed on a woven mat, placed in a woven basket, and, when a person died, he/she was placed on a woven mat an cremated. In between, woven baskets and mats were used for storage, carrying, cooking, and trade goods. A person’s life could be woven in the designs…….

A mostly peaceful people, the Haida and the Tlingit groups lived in relative isolation from the rest of the world, except for the occasional inter-tribal raids and, of course, trading. Trade goods were transported along the Inside Passage in these amazing canoes. This canoe was constructed using traditional methods from a single tree, hollowed out then stretched open to the familiar canoe shape.

The artwork depicts the myth of the Raven stealing the Sun. The Sun is crafted from a sheet of copper, which was used to denote value. An elaborate piece of artwork such as this might be created and gifted in a ‘potlatch’, a ceremonial gift giving celebration that was held to mark an important event. Wealth was amassed to be able to give more away, thereby increasing one’s social standing.

The Haida and the Tlingit peoples lived in this way until the early 1900’s, when they abandoned their subsistence way of life and move to more centrally located cities for employment. There is a movement, began in the 1970’s to help the native peoples rediscover and renew their culture through those crafts such as carving and weaving and ceremonial celebrations. The Totem Heritage Center has been a part of this, holding regular classes for aspiring artists.